In construction, robotics is often discussed in terms of technology: better AI, more capable machines, and robots on job sites. Recent research suggests that the question is less about whether robots can work and more about when and why they deliver real value.

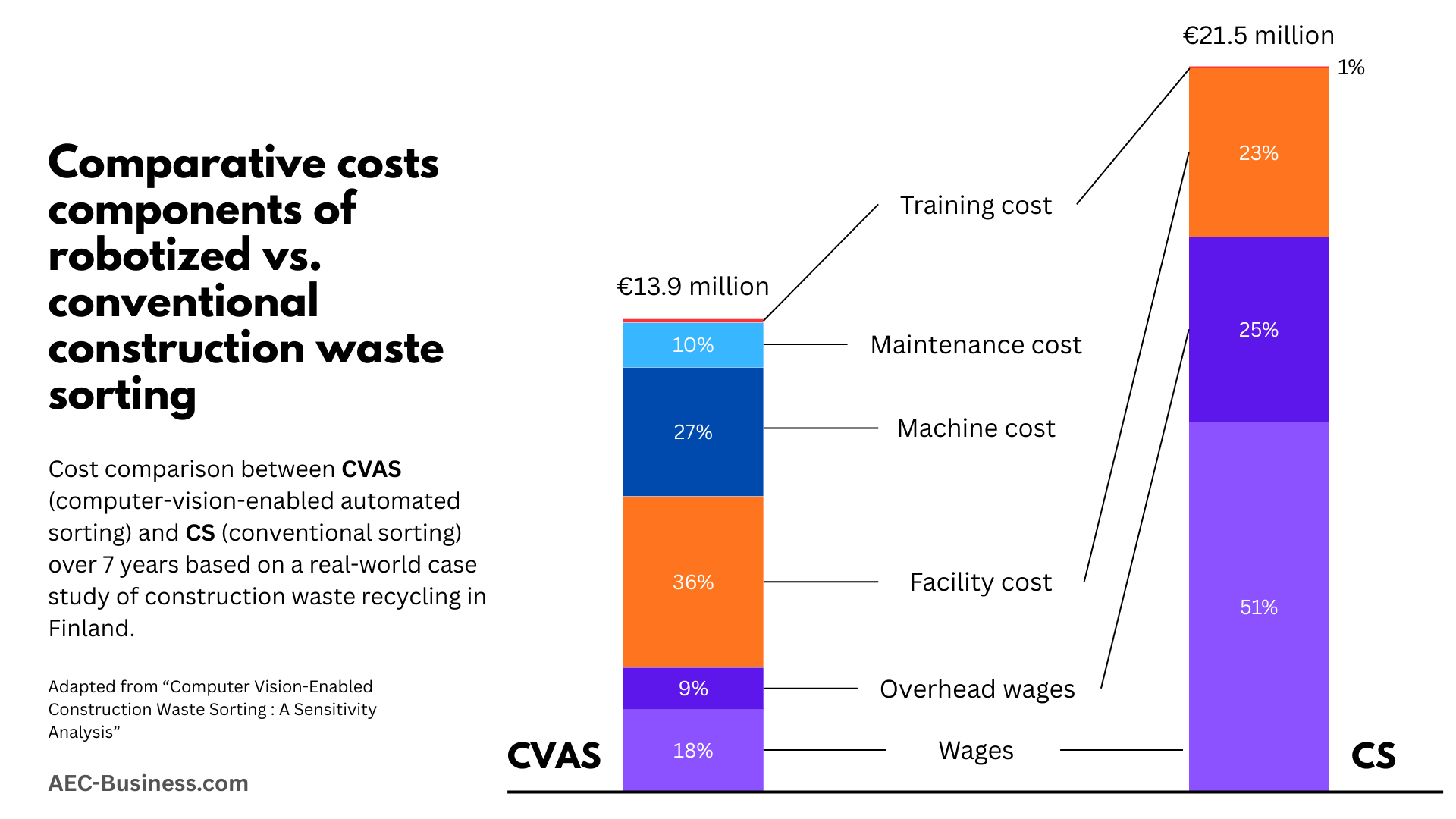

An Aalto University research paper on computer-vision-driven robotic waste sorting offers a valuable lens into this. The researchers use ZenRobotics’ computer-vision-enabled automated system as a case study. The Finnish startup was acquired by Terex, a U.S. company, in 2022.

At first glance, waste sorting might seem like a niche application. But it illustrates a broader economic logic that aligns with findings across the broader body of research on construction robotics.

Robotics as a cost and risk decision, not a cool tech choice

The most important insight from the Finnish case is not that robots can sort waste, since technology has been capable of that for a while. The real point is that, under certain conditions, robots make financial sense by reshaping cost structures, not because they are inherently efficient.

Robotic systems convert variable, unpredictable costs such as labor, with rising wages, training needs, turnover, and safety risk, into predictable, upfront capital and software costs. In the study’s model, when annual wages rise above roughly €21,000 per worker, the automated system becomes cheaper over seven years. This effect isn’t about speed; it’s about replacing cost volatility with predictability.

Too often, firms dismiss robotics simply because the upfront cost appears high. But if your financial models use strict payback periods and high discount rates, you systematically bias against automation, even when long-term value exists.

The importance of stable, repeatable workflows

One of the consistent themes in robotics research is that robots thrive when processes are stable and predictable rather than chaotic and ad hoc. Construction has inherent variability from unique sites, shifting sequences, and custom design. This variability is precisely what makes many robotic applications difficult.

But in settings where variation is limited and processes can be standardized, robots perform well. The Finnish waste line works not because the technology is magical, but because:

- material flows are continuous,

- tasks are repetitive,

- performance can be measured,

- variation is controlled upstream.

This applies to broader construction use cases. Robotics has the strongest traction in controlled environments like prefabrication yards and fabrication shops. There, the work resembles a factory more than an improvised site, and robots can succeed because inputs are predictable and tasks are repeatable.

Beyond waste sorting: Where robotics adds value

Waste sorting is only one example. Across research and pilot projects, you see the same underlying logic applied in other contexts. What matters is that the robots are assigned to defined, bounded tasks, not to open-ended problem-solving.

Material handling and logistics are a precise fit. Robots and automated vehicles can move, stage, and sort materials to reduce delays and on-site congestion.

Quality control and inspection benefit from robotics and computer vision because these tasks require consistency and documentation more than situational judgment.

Safety-critical tasks are another obvious area. Robots can take on physically demanding or dangerous work, such as drilling, demolition support, and repetitive lifting, reducing injury risk and long-term workforce strain.

A closely related and increasingly important domain is on-site robotic fabrication and 3D printing of building or infrastructure components. Here, robotics not only supports construction but also directly produces components. These systems shift work from manual assembly to automated execution, reduce material waste, and shorten logistics chains by producing components at or near the point of use.

Each case follows the same pattern from the waste study: robotics makes sense where the work can be stabilized, material flows are controlled, and digital design data can flow directly into production.

Humans and robots work together

Robotics does not realistically replace humans entirely. Research and field experience suggest the opposite: the best outcomes result from collaboration between humans and robots.

Successful deployments often position robots to handle the predictable, repetitive parts of a job while humans handle judgment, adaptation, and exception management. This matters not only technically but also socially. Workforce acceptance, training, and clear role boundaries are frequently cited as adoption enablers in empirical research.

Semi-autonomous systems, in which humans supervise or assist with robot functions, are also more widely adopted because they better align with the inherent variability of construction work.

Take a portfolio view

Many firms evaluate investments using project-centric financial models that emphasize short payback periods. These models lack mechanisms to capture value across a portfolio of projects. This is a structural mismatch with automation, which often delivers value over many job cycles rather than in a single isolated project.

Where firms have taken a portfolio view, aligned incentives, and invested in workflow standardization, robotics pilots have progressed to repeatable implementations.

Robotics as part of a data-enabled future

To realize value from robotics in construction, firms need to stop treating it as a standalone technology. Robotics should be seen as an integrated, data-enabled actor in the construction ecosystem, one that senses, measures, and feeds data back into planning, execution, and enterprise systems.

When robots are embedded in data flows and connected to BIM, project controls, quality systems, and AI, they become far more than machines. They become part of the “nervous system” of construction.

This integrated, data-centric view will ultimately determine whether robotics becomes a marginal add-on or a transformational force in how buildings and infrastructure are delivered.

P.S.

I previously wrote about the emergence of humanoid robots. Because they can mimic human behavior, could they one day replace task-specific, specialized robots and work more flexibly? The obvious answer is ‘no.’ They may work 24/7, but they ultimately share the same physical limitations as human workers. However, they expand the scope of robotic work and contribute to the overall development of AI-powered robotics.

View the original article and our Inspiration here

Leave a Reply